Tension and heated confrontations between successive leaders of the same party is not uncommon in the USA. Perhaps due to the dominance of two broadchurch parties, the method of selection via primaries, or the personalities of the involved candidates, US history has seen several consecutive candidates at loggerheads with one another.

Successive Party Leaders; Mitt Romney & Donald Trump

In 2016, outsider Donald Trump was on a warpath to the Republican nomination for president. That year, Mitt Romney became an outspoken opponent of Trump’s bid for the presidency, famously remarking that Trump was “a phony [and] a fraud.”

In the Utah caucus, he tactically voted for Trump’s biggest rival Ted Cruz. Despite his hesitance towards Cruz, he was reportedly thinking about running on a third-party ticket with Ted to derail Trump’s chances according to the book Romney: A Reckoning.

In 2018, Romney won election to the Senate, where he would become the biggest anti-Trump voice in Congress.

In 2020, Romney made history by becoming the first senator to ever vote against a president of the same party when supporting Trump’s impeachment. In 2021, he again attempted to impeach Trump after January 6th, remarking that Trump had led “an unprecedented attack against our democracy” due to his “selfish…injured pride.”

In Trump’s post-presidency afterlife, he has continued to attack No. 45, including labelling him a RINO over his calls to rip up the Constitution and his criminal indictments.

He added he would prefer to vote for a Democrat than allow Trump back in the White House, having also not voted for him in 2016 or 2020.

Trump meanwhile, has largely brushed off comments from Romney, retaliating by calling him a “failed presidential candidate”, a “pompous ass”, and a “total loser.” Due to the power disparity between

He is not the only Republican to go against Trump, with John McCain voting against Trump in 2017, shooting down a campaign pledge to repeal Obamacare.

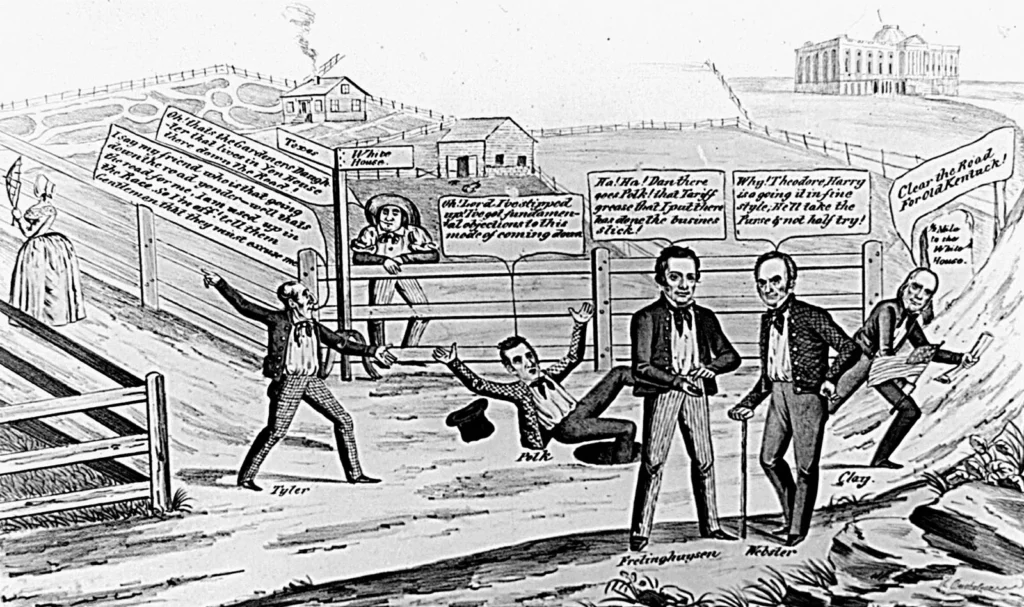

Successive Party Leaders; John Tyler & Henry Clay

In 1841, just a month after being inaugurated, President William Henry Harrison died. The first premier to die in office, Vice-President John Tyler used the ambiguous text in Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 to propel himself to the US’s top elected office.

Perhaps this contentious rise was the start of his heated confrontation with Henry Clay, a stalwart of the Whig Party in Congress, having run for president in 1824 and 1832.

Once in office, John Tyler refused to re-establish a national bank, which had been one of the major priorities of Whigs such as Clay. The bill was sent to Tyler where it was vetoed, in line with Tyler’s states’ rights sympathies. Another modified piece of legislation was sent to the president’s desk where it was again vetoed.

Clay supporters threw stones, shouted that he was a traitor and hanged and burned the president’s effigy. Clay gave the remark: “Tyler dare not resist; I will drive him before me” in a threatening message.

Such an out-of-step and perceived authoritarian use of the veto did not sit well with the Whigs who ousted the incumbent president, leaving him without a party.

In September, Clay was personally behind an orchestrated mass resignation from Tyler’s Cabinet in which all but one member walked out.

According to the book The Presidencies of William Henry Harrison and John Tyler, Clay’s anger seemed more personal as “more than Clay wanted a bank, he wanted to bring down Tyler.”

In 1842, Clay – already a favourite for 1844 nomination by this stage – stepped back from the Senate. He would speak out later against Tyler’s annexation of Texas.

Perhaps in vengeance, Tyler backed pro-annexation Democrat James K. Polk in 1844, believing his tenure would be a continuation of his presidential direction.

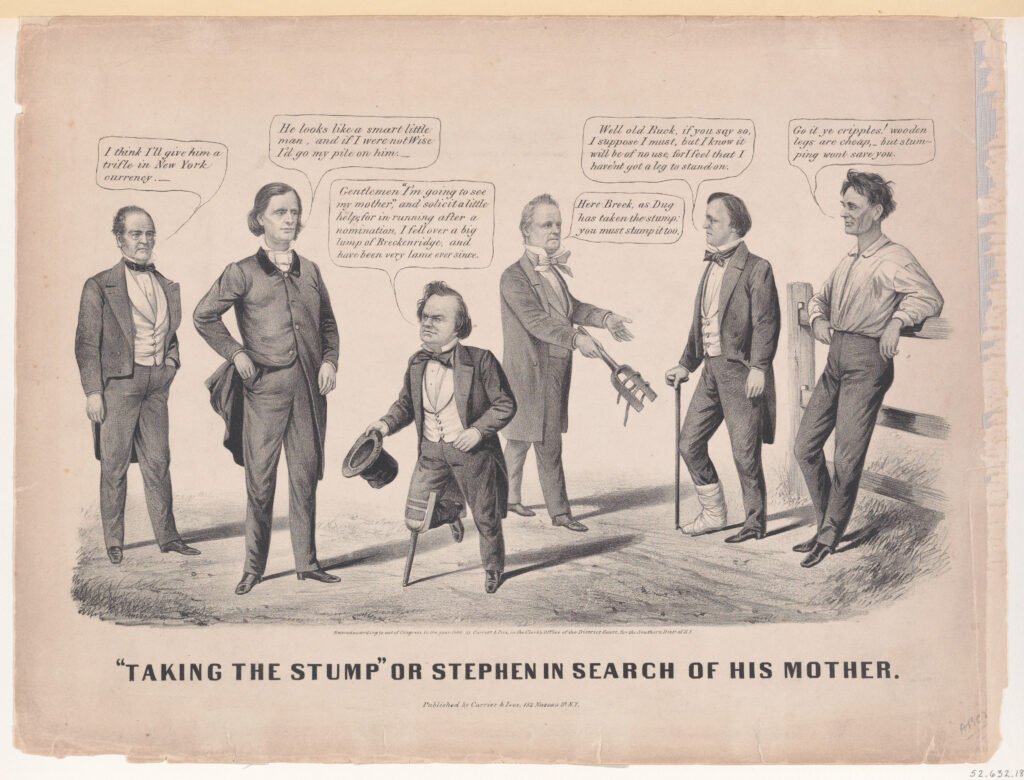

Successive Party Leaders; James Buchanan & Stephen A. Douglas

The 1860 presidential election is arguably the most important in US history. In that contest, the Democrats were convincingly trounced, in part due to divisions within the Democratic Party.

During James Buchanan’s presidency, he clashed with popular Senator Stephen A. Douglas over the issue of slavery.

Buchanan wanted all Democrats to support the Lecompton Constitution when put before Congress. In this, a state constitution for Kansas designated Kansas as a slave state with provisions to protect slavery. Seeing it as odds with his belief in popular sovereignty, Douglas objected, believing it was up to the citizens to choose their status on slavery.

He too was likely considering his re-election chances in 1858. In his home state of Illinois, 55/56 newspapers had denounced the concept.

In return, Buchanan threatened Douglas, one of the leaders of the northern Democrats, retorting: “I desire you to remember that no Democrat ever differed from an administration of his own choice without being crushed.”

It was not the first conflict between the two. Indeed, author Damon Wells notes Buchanan worked against Douglas in 1852 whilst the president snubbed him from his Cabinet after being elected.

The so-called “Little Giant” railed against the president, calling the proposal a “fraudulent submission” which he would “resist to the last.”

In his famous 1858 re-election, in which Douglas participated in the famous Lincoln-Douglas debate, Buchanan seemed happy to sink his own party’s ship by standing pro-Buchanan Democrats which could hand the seat to the Republicans.

It ultimately failed as Douglas prevailed and became the 1860 Democratic candidate, his profile heightened by printed transcripts from the debates.

However, the divisions seriously blighted the party’s chances. The Republicans prevailed whilst the Democrats won just one state and 12 ECVs. Buchanan backed Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge; he won 11 states and 72 ECVs.

With Lincoln’s win, several southern states succeeded and the Civil War was under way within months – perhaps unlikely had two men not despised one another so much they split their party.

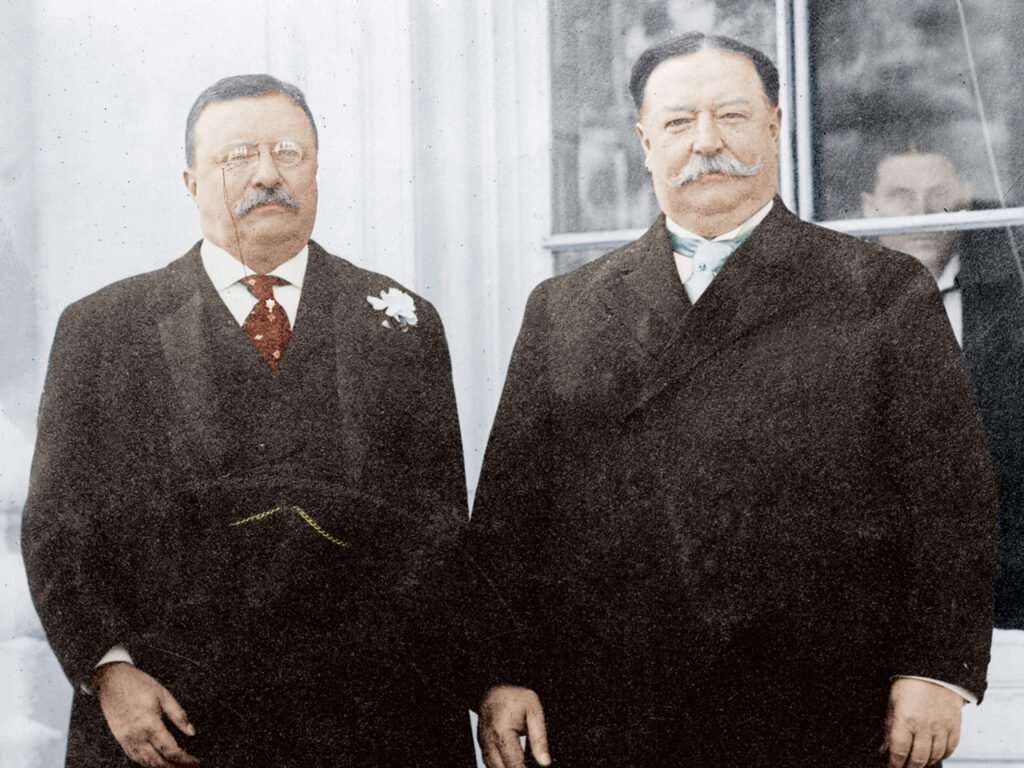

Successive Party Leaders; Theodore Roosevelt & William Howard Taft

When departing office in 1908, Theodore Roosevelt prepped William Howard Taft to take over the reins of the presidency.

Yet the problems started early on when Taft did not consult the former president about Cabinet appointments.

After returning from an African expedition, Roosevelt set out his New Nationalism ideas, subtly attacking Taft over his increased conservativism, which was at odds with Roosevelt’s progressive policies.

Although initially reticent, Roosevelt broke a previous pledge not to run for a third term and staged a challenge against Taft. He told supporters in a speech: “We stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord”.

Despite winning 10/12 of the state primaries, delegates and party establishment overwhelmingly chose Taft; on the convention floor, fights broke out between pro-Roosevelt and pro-Taft delegates, showing the heated state of affairs between the two. Roosevelt accused Taft of breaking the eighth commandment by stealing the nomination.

The campaign was tense, with the fighting branches of the Republican Party making Democrat nominee Woodrow Wilson something of a third wheel, even if he easily strolled to election in a rare Democratic presidential victory for the timeframe.

The Progressive (or “Bull Moose) Party ran on an incredibly liberal platform, championing social insurance programs, an eight-hour workday, women’s suffrage, a national minimum wage, and health insurance. Taft criticised some of the party’s policies, calling their court-curbing plans the actions of “political emotionalists or neurotics.” He too warned that his “arbitrary character” would do “irremediable injustice to private right.”

In the election, Taft’s vote tanked. Progressives knocked him off the ballot in California and South Dakota, both of which he had won the previous election. He suffered the biggest loss the party had ever faced and, to this day, the worst performance of an incumbent president.

Successive Party Leaders; Al Smith & Franklin D. Roosevelt

The change in results from 1928 to 1932 for the prospects of the Democratic Party is the most drastic turnaround in US history. In 1928, the party won 87 Electoral College Votes (ECVs) and 8 states; in 1932, they won 472 ECVs and 42 states – both landslides albeit in opposite directions.

1928 saw Franklin D. Roosevelt win New York’s gubernatorial election, able to tide off the Republican landslide. FDR’s victory was in contrast to Smith’s loss in New York, which was his home state.

Despite being friendly in 1928, by the 1932 Democratic Party convention, Smith was heading up efforts to block Roosevelt’s nomination.

As to why, it has been suggested that he felt Roosevelt had slighted him. Smit felt Roosevelt had ‘big timed’ him, rejecting his advice or policies once governor and removing Secretary of State Robert Moses against the 1928 candidate’s wishes.

Notably, Roosevelt’s ‘The Forgotten Man’ speech turned Smith “incandescent with rage,” soon after promising to “take off my coat and vest and fight to the end against any candidate who persists in any demagogic appeal to the masses.”

Some think the reason was more personal. 1928 saw Smith stand little chance of winning but a Democratic win in 1932 was a foregone result, with Smith believing he deserved a second run after his minimal chances last time round. Yet FDR was the frontrunner, with 1928 running mate Joseph Taylor Robinson backing him. His block of Roosevelt would have ruled out his biggest opponent and let him be a virtual sue-in for the presidency. Even 1928 running match Joseph Taylor Robinson backed FDR.

He was a continued critic during the presidency, some attributing it to bitterness and jaundice.

Smith joined the American Liberty League, which railed against “alphabet soup” New Deal policies, such as “fascist control of agriculture” and anti-democratic Social Security. In 1937, he bemoaned $100 million worth of “senseless, useless, fruitless” spending.

It was not entirely hostile, with Smith remaining friends with FDR’s wife Eleanor and Roosevelt being, in the words of Terry Golway, “admirably gracious” to Smith, sending a heartfelt letter in 1944 after the death of Al’s wife.

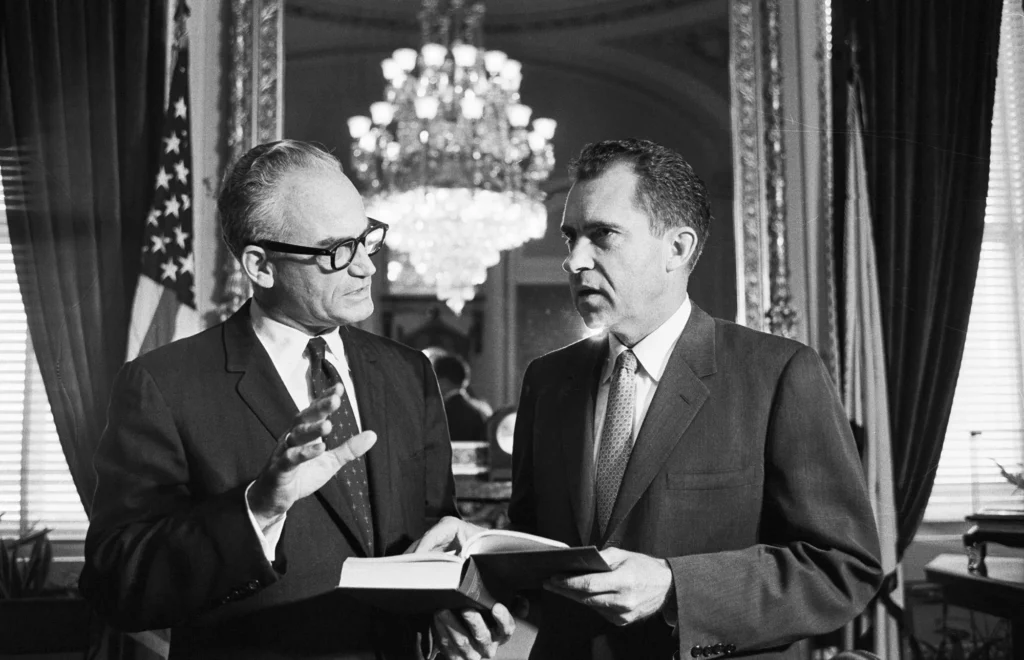

Successive Party Leaders; Barry Goldwater & Richard Nixon

Initially, it seemed there was little ill will between Republican nominees Goldwater and Nixon. Although politically unique from one another, the two were willing to support each other during their presidential campaigns.

However, by 1974, the Watergate crisis saw tensions rise to the surface.

Prior to this, the relationship had seen some small dents, with The New York Times running an article titled “Goldwater Rift with Nixon Deep.” On another occasion, Nixon subtly chastised Goldwater by saying the 1964 election was lost due to “a rejection of reaction, a rejection of racism, [and] a rejection of extremism.”

In late 1974, Nixon – coming under increased pressure from the Watergate scandal – lost Goldwater’s public support. In an interview with NBC’s Today show, when Nixon was on a foreign excursion, Goldwater proclaimed that: “As far as I’m concerned, Mr. Nixon can go to China and stay there.”

Nixon resigned less than a week after losing his public support. It was also Goldwater who was designated by his Republican colleagues to tell the president he had lost their support and would lose an impeachment vote. This was his only notable role in the Nixon administration.

Nixon apparently retorted “I have nothing this morning but the deepest contempt” for Goldwater and Congressional Republicans.

Goldwater has continued to be deeply critical of Nixon since. In his memoirs, he commented: ““He was the most dishonest individual I ever met in my life.” He added, “President Nixon lied to his wife, his family, his friends, longtime colleagues in the US Congress, lifetime members of his own political party, the American people and the world.”

In an interview, he concluded that “All Dick Nixon was interested in was Richard Milhous Nixon.”

When President Nixon died, Goldwater was told not to make a statement in case it was viewed as disrespectful, having previously espoused the view he had no respect for him. Goldwater was not at the funeral.

GRIFFIN KAYE.