Of course, the English language – one of the largest in the world – is forever evolving so the creation of new words is simply inevitable but some have more surprising backstories than others. So, here are the truly intriguing origins of 10 English language terms, including Meme, Unfriend, Nerd and…

Okay

Not too many words rise to fame via a presidential campaign but such is the case with the term ‘okay’. Perhaps one of the most commonly used words on a day-to-day basis, the term ‘okay’ can be used as an acknowledgement, a seal of approval, a discourse marker and all matter of other roles. The acronym was used as far back as the 1830s in the then-newly established United States. Initially, educated Americans used deliberately misspelt abbreviations to try and dupe the less-knowledgable.

These are called cacography; examples include ‘KC’ (‘Knuff Ced’), ‘KY’ (‘Know Yuse’) and ‘OW’ (Oll Wright’). ‘OK’ was the only one that would ultimately stand the test of time, originally standing for ‘Oll Korrect’, although the spelling of the term varies from source to source.

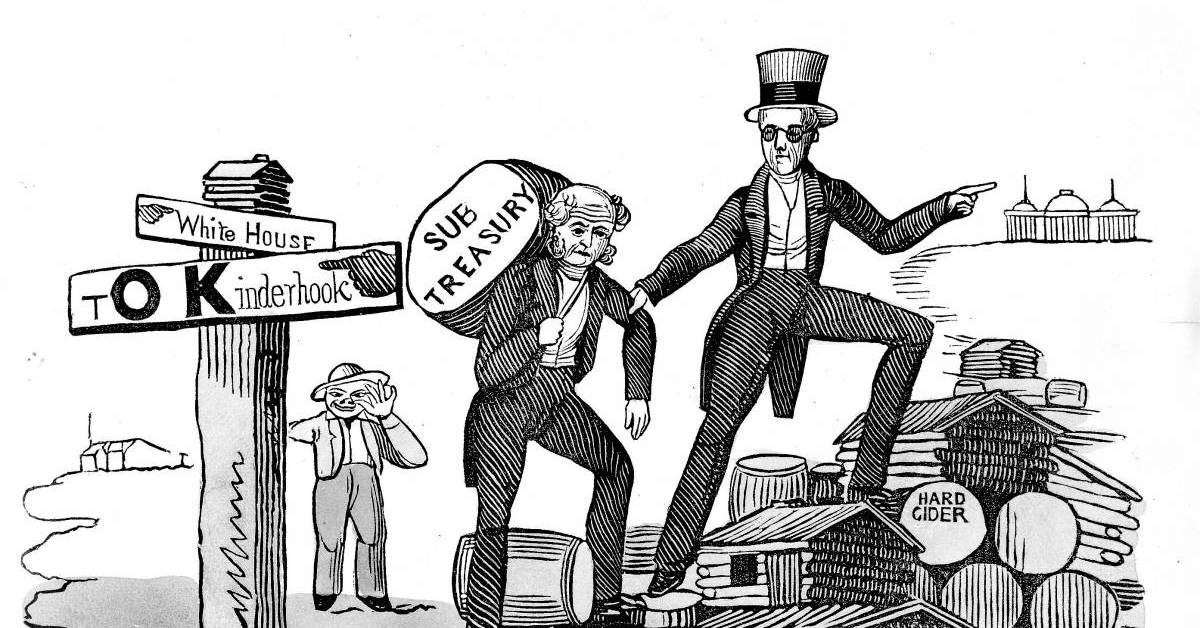

Despite appearing for the first time in published media in March 1839 in the Boston Morning Post, it would not gain national attention until the 1840 presidential election. At the time, the president was Democrat Martin Van Buren. The eighth US president was nicknamed “Old Kinderhook”, an allusion to his New York birthplace.

As a result, his supporters formed the OK Club. This prompted the slogan “Old Kinderhook is OK”, although oppositions used it to mock Van Buren, changing it to stand for ‘Orful Katastrophe’ and similar phrases.

In the end, MVB still lost the election to William Henry Harrison. It was a win for ‘OK’ however. A few years later, the message became essential for use of the telegraph as a quick, uncomplicated and unmistakable communication term. As the word developed, it has become its own stand-alone word, with the more formal ‘Okay’ spelling developing.

The word is still to the day slapped all across marketing, and for the word, businesses can thank one of the US’s most forgotten US presidents.

Meme

Today, everything from Grumpy Cat to excerpts from He-Man to Rick Astley’s ‘Never Gonna Give You Up’ are dubbed ‘memes’, yet the term actually was coined back in the 1970s. In 1976, British evolutionary biologist and all-around God-basher Richard Dawkins published his book The Selfish Gene.

As well as establishing the gene-centred view of evolution in which he outlines “all life evolves by the differential survival of replicating entities”. In addition, he introduces the term ‘meme’.

Dawkins used the word to describe a unit of cultural information spread by imitation. This was taken from the Greek term ‘mimema’, meaning imitated. Speaking more specifically, Dawkins refers to catchphrases, fashion and general cultural trends easily spread across a mass region of people.

According to Google’s Ngram Viewer, the word grew from the 1990s onwards and peaked at the most recent date labelled: 2019, showing the word’s continual growth. Ironically enough, the word ‘meme’ has itself become somewhat of a meme.

It does seem of truly weird origin that one of the world’s greatest living authors and intellectual minds would create one of the strangest parts of popular culture. Speaking of the meme, Dawkins has said: “The meaning is not that far away from the original. It’s anything that goes viral. In the original introduction to the word meme in the last chapter of The Selfish Gene, I did actually use the metaphor of a virus. So when anybody talks about something going viral on the internet, that is exactly what a meme is and it looks as though the word has been appropriated for a subset of that”.

Unfriend

Similar to the last entry, ‘unfriend’ too seems as if it was coined in the modern technological world but is much older than that. Despite the term growing thanks to social media – particularly the very, very data-protective app Facebook – the word’s first recorded use as the verb we know today from a computerised world was back in the 17th century.

The first use of the term in its verb form in print was way back in 1659. In a letter from theologist Thomas Fuller. In this, he wrote to a colleague: “I hope, sir, that we are not mutually un-friended by this difference that hath happened betwixt us”.

It was actually also used by Shakespeare, albeit not as a verb as is familiar to us today. King Lear, first performed in 1606, states, “unguided and unfriended, often prove. Rough and unhospitable” – this uses the term instead as an adjective, meaning to be going alone, without friends.

From its first official usage as it would be today – as well as even earlier usage by Shakespeare – it is surprising that this now commonly-used Facebook term was first documented before the Great Fire of London, the London Plague and the birth of George I.

Boredom

It is a commonly-cited fact that ‘boredom’ was coined by none other than Charles Darwin and although a neat bit of trivia sure to not bore people, it is not true. The story goes that the first use was in Dickens’s 1852 work Bleak House.

In this, the word is used 6 unique times, with the first reading that “only last Sunday, my Lady, in the desolation of Boredom and the clutch of Giant Despair, almost hated her own maid for being in spirits”. The concept of being bored had been around prior, with the French term ‘ennui’ – a term originally meaning one of annoyance – being used post-1770s.

The first actual documented use is 23 years before Dickens. This was in an edition of The Albion on August 8th 1829 in which the author wrote that “Neither will I follow another precedental mode of boredom, and indulge in a laudatory apostrophe to the destinies which presided over my fashioning”.

Dictionary.com goes into further detail on other supposedly Dickensian terms not coined by the author of A Christmas Carol, A Tale Of Two Cities and Great Expectations, these include:

- An 1835 issue of Waldie’s Select Circulating Library using the term ‘butterfingers’ a year before Dickens’s work of The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club, better known as The Pickwick Papers.

- In that same piece, Dickens supposedly created the term ‘flummox’ but this too is incorrect as Miriam-Webster dictionary states the first use was in 1832, at least 5 years before the work of Dickens.

- ‘Devil may care’ too is credited to Dickens, a shortening of a longer idiom. The phrase was used in several texts before C.D., including The Commercial Observer in 1836 and L.L. Leatrwick in 1823, with earlier even uses, albeit in different forms.

That said, an 1839 edition of The Quarterly Review summed up the writer rather effectively described Dickens as the “regius professor of slang”, as the author had his ear to the ground in terms of local dialects and idiolects of cities. In doing so, he had the first known usage of less-commonly-used words like ‘sawbones’ and ‘metropolitanteously’. That said, Dickens did not invent ‘boredom’, although he would aid the correct use of the term as well as to popularise it to a larger audience.

Quiz

A story from 1791 tells us that the word ‘quiz’ comes from a bet. In this, a theatre proprietor in Dublin called Richard Daley launched a bet that he could get a new word into common parlance within 24 or 48 hours – depending on the story.

He commissioned a legion of street children to write the nonsense term all across the city where people, unknowing what the term meant, created their own interpretations. This is commonly disregarded however as an urban legend, as it was printed before this including in The London Magazine in November 1783: “it will be difficult to say who shall be termed a Quiz, and who shall not: each person indiscriminately applying the name of Quiz to everyone who differs from himself”.

The official etymology is unknown although it was used to initially describe a hoax or a strange person.

‘Inquisitive’ has given way to the use of ‘quiz’ being used in unique ways such as for a policeman to ‘quiz’ a suspect or to be given a ‘quizzical’ look. No matter the origin, the story from 1791 has been mostly rejected but has now become a term, without real reason, for a test or examination on a basis of knowledge, still commonly played at bars, pubs and inns – perhaps reflecting its origin.

Flange

You are likely not too familiar with the term ‘flange’, that is, unless you are well-versed in the world of pluralisations, specifically of baboons.

The term ‘a flange of baboons’ has become an increasingly popular and widely-used term, likely due to an unofficial or unspecific term used beforehand. The origins of this term are truly bizarre.

‘Flange’ comes from a famous sketch on Not The Nine O’Clock News. The sketch in question, Gerald The Gorilla, sees Mel Smith portray a professor who has managed to tame and sophisticate a gorilla, played by Rowan Atkinson. The professor comments that “Well, to begin with, Gerald did make various attempts to contact his old flange of gorillas . . .” before he is interrupted by the irritant gorilla who retorts, “It’s a whoop, Professor, a whoop of gorillas. It’s a flange of baboons, for God’s sake”.

The word has since developed into an acceptable term to refer to a collection of baboons, even used by academics. A review of Barbara B. Smuts’s journal Sex And Friendships in Baboons reads “In this marvellous book, Smuts draws from years of painstaking field research in which she followed around a flange of chacma baboons in the Mateti Game Reserve in Zimbabwe”. Also, a book titled Mess Of Iguanas, A Whoop Of Gorillas…: An Amazement Of Animal Facts was published in 2009 by Alon Shulman, documenting strange but true animal names. These illustrate how random, made-up terms from a comedy sketch have infiltrated common usage.

Nerd

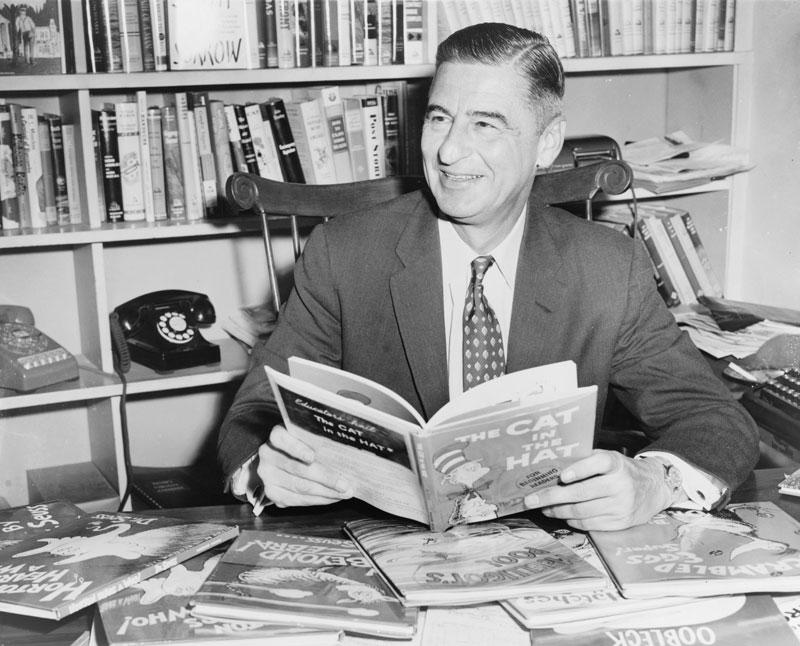

The term ‘nerd’ originates in 1950 in Theodore ‘Dr Seuss’ Geisel’s whimsical work If I Ran The Zoo. In the book, the lines: “And then, just to show them, I’ll sail to Ka-troo/And bring back an It-kutch, a Preep and a Proo/A Nerkle, a Nerd, and a Seersucker, too!” is used – the first printed use of the word.

In October the next year, ‘nerd’ would be published in an edition of Newsweek. The author wrote about the latest slang term of Detroit: “someone who once would be called a drip or a square is now, regrettably, a nerd”. The term ‘nerd’ grew in popularity in the ‘60s and garnered further recognition after its use in the TV show Happy Days. In this, Potsie Weber was often referred to by the saying due to his awkward socialising and lack of perceived coolness.

The actual etymology of ‘nerd’ has been speculated upon since its inception. This includes being named after ventriloquist dummy Mortimer Snerd or a derivative of the common 1940s term ‘nerts’, coming from ‘nuts’ – meaning a crazy or deluded figure.

According to Google’s Ngram Viewer, the word has shot up in the usage of publications since 1980. This includes tripling by 1990 and octupling by 2020, having seen no growth before 1980.

Sabotage

The origins of the term ‘sabotage’ are often shrouded in misconception and falsehoods.

The actual origin is from the French word ‘saboter’. This word was originally used to refer to rural workers, these would often don clogs rather than more conventional, city-based shoes. Yet these textile workers were slow and inefficient, leading to the derogatory term ‘saboteurs’. This term would then refer to bungle and affect the word rate of production.

In 1907, The Liberty Review would document the word, saying: “SABOTAGE [chapter heading] The title we have prefixed seems to mean “scamping work”. It is a device which, we are told, has been adopted by certain French workpeople as a substitute for striking. The workman, in other words, purposes to remain on and to do his work badly, so as to annoy his employer’s customers and cause loss to his employer”.

The other story stems from the Industrial Revolution. The French equivalents of Luddites, much more violent than English Luddites, took place in labour protests in cities like Lyon. Dissatisfied by the jobs being lost by the implementation of these new technologies, these workers threw their clogs or ‘sabots’ in French into the machinery, thus hampering and deliberately foiling the machines from carrying out their function. These saboteurs’ actions would lead to the term in which something is ‘sabotaged’ so is purposely hindered.

Whilst interesting, the latter does seem to be false; the noun’s first known use was in 1910 and as a verb in 1913.

Boy

Before the 16th century, both boys and girls were called girls. In fact, what we now call ‘boys’ were called ‘knave girls’ whilst girls were ‘gay girls’ – a rather confusing concept to modern ears. ‘Boy’ was a term in use but meant as in a waiter, servant or butler, who was often a young gentleman.

Interestingly, male babies would also dress in pink and girls in blue. A stark contrast to society today, this continued into the 20th century. In 1900, Dressmaker Magazine authored an article which read: “The preferred colour to dress young boys is in pink. Blue is reserved for girls as it’s presumed paler and the more dainty of the two colours and pink is thought to be stronger”.

As for the term ‘boy’, it would peak massively in the mid-1560s according to Google’s Ngram viewer. ‘Boy’ would almost permanently be more commonly used than ‘girl’ until the 1970s, to which ‘boy’ has never managed to overtake ‘girl’ and reclaim its top position.

Both ‘gay girl’ and ‘knave girl’ fell into disuse afterwards. Whilst ‘gay girls’ was not used post-1500 until 1729, ‘knave girl’ was not used until 1896 (the first year of the modern Olympic Games).

Jail

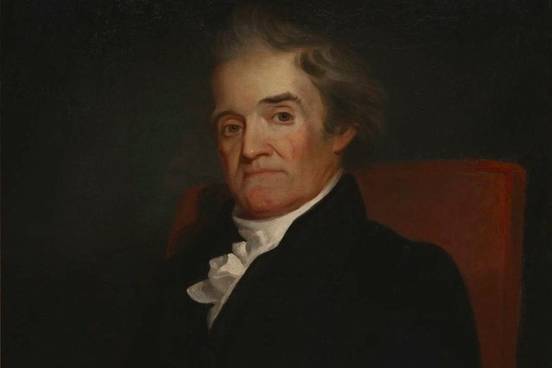

The differences between British English and American English are well-established. US citizens have made various alterations to British terms, including changes influenced by lexicographer Noah Webster such as removing the ‘u’ from already-used words like ‘colour’, ‘humour’ and ‘honour’ – all used before the US Declaration of Independence of 1776 by Isaac Newton, Jonathon Swift and William Shakespeare respectively.

It is less common however for American adaptations of British words to become the primarily used version in the UK.

From Latin, the French had 2 terms for what we now call a ‘jail’, these being: ‘jaiole’/’jaile’ in Partisan French and ‘gaiole’/’gayole’/’gayol’ in Northern France; the latter derivate was used by the English. British law saw ‘gaol’ used as the term to refer to prison although the aforementioned Noah Webster favoured the ‘jail’ spelling as far back as his 1806 dictionary.

The fame of the g-starting spelling was further popularised by works such as Oscar Wilde’s 1898 The Ballad Of Reading Gaol. In this, the Irish writer documented his time in prison for the crimes of gross indecency and sodomy. It was his last official work published in his lifetime.

The US spelling caught on only in the USA originally, with the USA spelling taking over in the 1820s. In the whole English language, it was just before 1850 that ‘jail’ became the most populous use. Yet in the UK, ‘jail’ would not have overtaken the more popular English term until 1965, influenced by application in the likes of Elvis Presley’s song and subsequent film Jailhouse Rock.

‘Gaol’ has continued to plummet in recent years. Although still correct to use, it only really refers to prisons of times long gone by. “Each man kills the thing he loves” indeed!