A former member of the Communist Party (explaining they were the only party “unambiguously against Hitler,”) he made an explosive speech at the 1945 Labour conference, savaging the “selfish, depraved, dissolute, and decadent” upper class.

Denis Healey was elected to Parliament in 1952 in the safe seat of Leeds South East.

In 1955, he would be elected to Leeds East where he remained the MP until 1992.

In the 1963 Labour leadership election after the death of close associate Hugh Gaitskell, he voted for James Callaghan. Despite being in the right-wing Gaitskell camp, he would vote for ex-Bevanite Harold Wilson after Callaghan was eliminated.

Under Wilson, Healey would be made Shadow Defence Secretary, becoming Defence Secretary after Labour’s victory in the 1964 election.

In stark contrast to the nine Defense Ministers in the previous 13 years, Healey’s tenure would be the longest in the role’s history at nearly six years.

Once describing the job as “the thing I enjoyed the most,” it was common he would work 16-hour days.

Healey was responcible for reducing Britain’s defence forces both militarily and economically. A 1967 White Paper advocated the withdrawal of bases east of the Suez Canal but he nonetheless pledged to “never deny Britain the role of a world power”.

He also oversaw Rhodesia’s declaration of independence – the UK’s first unilateral independence treaty since 1776 – and was a vital voice in preventing UK involvement in the Vietnam War.

He has credited his success in Borneo as being his greatest political achievement. In the conflict, just over 100 British troops died in what Denis described as “one of the most efficient uses of military forces in the history of the world.”

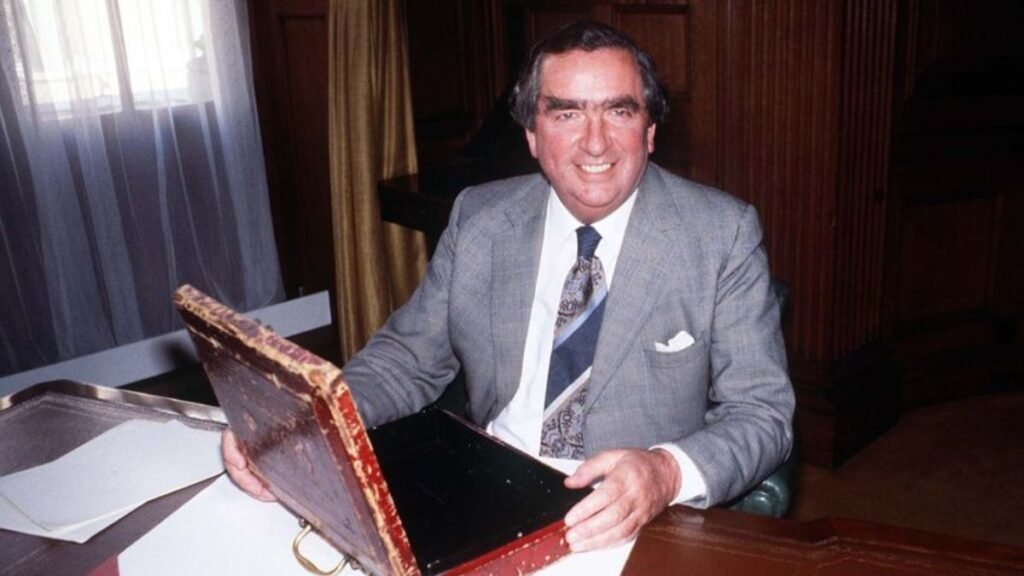

In 1972, Roy Jenkins resigned after disagreements over the European Economic Community, with Healey filing in the spot. In Opposition, he was a divisive figure, reportedly promising to squeeze the rich until “the pip’s squeak.”

By 1974, Labour again took power and Healey raised corporation tax, the last Labour government to ever do so and the last Chancellor until Rishi Sunak in 2021.

During his time in the role, he faced left-wing backlash, being removed from the Labour National Executive in 1975.

The next year, he ran for Labour leader after Harold Wilson where he came fifth. Despite this, he fought on in a race won by James Callaghan. After a short period in the role, he made an extremely contentious decision when he sought a loan from the International Monetary Fund. At £3.9 billion, the agreement came as the sterling was plummeting, having fallen 20% since Callaghan came to power. At the same time, inflation was at an eye-watering 25%.

Such a decision required sharp cuts in public expenditure and wage controls. As such, he can be seen to have ditched the Keynesian economic post-war module before Thatcher ever did.

As political scientist Vernon Bogdanor commented: “Perhaps he was both [a] hero and villain.”

After Labour lost the 1979 election, Healey seemed the favourite to win the party’s leadership race. Given 4-5 odds of winning by Ladbrokes, he had topped the 1979 Shadow Cabinet elections. Plus, public opinion polls had placed Healey as the nation’s preferred prime minister over Margaret Thatcher.

When it came to the event however, he was edged by socialist candidate Michael Foot. Although Foot was more radical, it was thought his less confrontational approach could ease a disjointed party.

Healey was unopposed in becoming Deputy Leader but was given a fierce challenge by Tony Benn. The bleeding-heart leftist’s attempt failed by just 0.4%. Healey won by, in his own words, “a hair of [his] eyebrow.” “Hurricane Healey” also served as Shadow Foreign Secretary.

Although he spent much time fighting the extremists, he was still as biting towards Margaret Thatcher, stating she was “glorifying in slaughter” over the Falkland War and comparing her to “an old bag lady, muttering imprecations at anyone who catches her eye.”

When the Social Democratic Party formed, Healey stood firmly with Labour, believing a defection would make a progressive government untenable.

The 1983 election campaign has been described by political commentator John O’Farrell as “the worst campaign in electoral history,”; Healey espoused a similar view in his memoirs. Additionally, the party’s manifesto featured elements Healey had publicly denounced, such as nuclear disarmament. The party suffered its worst result in the post-war era, winning just over 200 seats as the Conservative Party attained a 144-seat majority.

Healey did not stand in the leadership contest, which would be won by Neil Kinnock. He continued to hold the post of Shadow Foreign Secretary until the 1987 election, at which point he stood down from the role. He left Parliament at the 1992 election; also leaving that year were his contemporaries Michael Foot, Margaret Thatcher, and Geoffrey Howe, amongst others.

Upon John Smith’s death in 1994, Healey was the first Labour politician to publicly support Tony Blair’s leadership bid. Despite this, he would call for him to resign during his premiership. He later remarked: “with the intervention in Iraq, then university entrance fees, and foundation hospitals…the sooner Gordon Brown takes over the better.”

In October 2015, Healey passed away. At the age of 98, he was the oldest sitting member of the House of Lords. He was also the final surviving Cabinet minister from the first Wilson ministry comprised in 1964.

Former opponent Tony Benn paid tribute to Healey, calling him: “a stalwart of the Labour Party, a true patriot who fought for and cared deeply about his country and an extraordinary and vibrant character.”

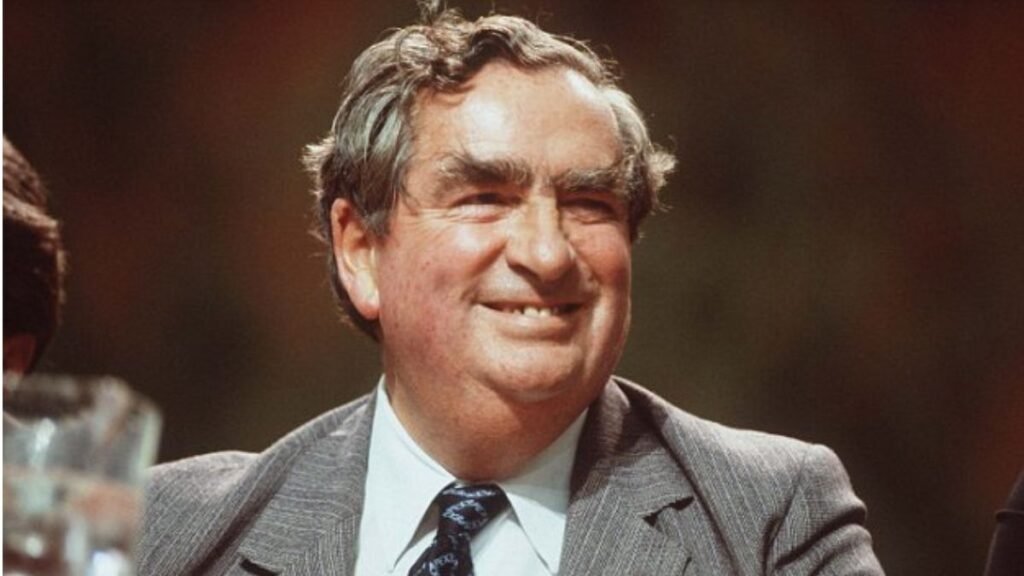

Healey’s legacy was exemplified throughout his career by his character; the bushy eyebrows, chirpy outlook, and bruising hostility.

He had a noteworthy TV career as the only Chancellor to appear on The Morecambe and Wise Show, dancing with Roger Moore, and featuring on This Is Your Life. His famous “Silly Billy” catchphrase was taken from impressionist Mike Yarwood, who often parodied Healey.

To this day, Healey is often bequeathed with the title of the best prime minister we never had. [1,000 words]

GRIFFIN KAYE.