“I spend my cash on looking flash and grabbing your attention” is the opening line of ‘Stand And Deliver’ by Adam & The Ants. In the modern era, the highwayman has been romanticised beyond reality, with these street thugs seen as suave and classy individuals despite their status as criminals. Of these, one of the most famous is Dick Turpin and if there is one thing I like doing here at TWM, it is fighting for social justice so it is time to dispel the Dick Turpin myth – not an honourable and idyllic countryside anti-hero but a murderous felon who ruined the lives of many.

Life & Crimes Of Dick Turpin

By the mid-1930s, Dick Turpin had become a known name in the criminal underworld, joining the notorious Gregory Gang, the Essex-based conglomerate of tyrants.

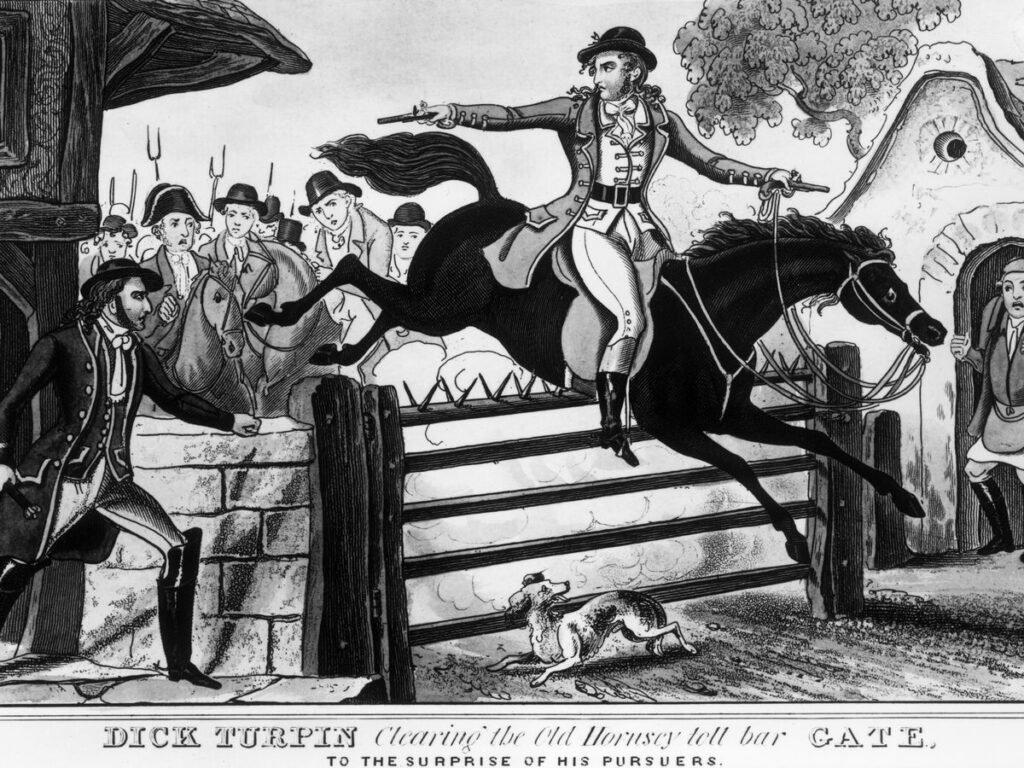

Turpin started in the butchers’ trade, illegally selling stolen game, poaching for meat. Turpin raised suspicions so he decided to flee, abandoning his wife and running away from the Essex gang, robbing people as he did so. As author Stephen Basdeo commented in Essex Live, “They certainly did steal from people around Epping Forest but…rarely robbed people on the road. Contrary to popular myth, they rarely stopped stagecoaches. They were pretty cowardly and went for lone travellers.”

It is even thought Turpin killed a partner Matthew King during a botched robbery before escaping the scene.

Dick’s robberies were barbaric enough to consider his status as a heroic rogue. One of the stories includes Turpin beating a 70-year-old farmer with a pistol and pouring a kettle of boiling water over his head until he confessed where the loot the criminals wanted was, all as another member raped a housemaid. All the group got from this was £30, or a few thousand pounds today. At 26, this ‘charming’ man too was riddled with smallpox according to The London Gazette.

Highwayman Turpin made an error in May 1737, shooting Thomas Morris to death with a carbine in Epping Forest after attempting to capture Dick. The Gentleman’s Gazette described Turpin as “about Thirty, by Trade a Butcher, about 5 Feet 9 Inches high, brown Complexion, very much mark’d with the Small Pox, his Cheek-bones broad, his Face thinner towards the Bottom, his Visage short, pretty upright, and broad about the Shoulders.” A large reward was offered for his capture.

Under the alias John Palmer, Turpin continued his life of crime, shooting and stealing animals, which had been capital offences for hundreds of years, ones punishable by death. He shot and then threatened the cock’s owner at gunpoint. Turpin was not above threatening young girls and old women.

Palmer’s fate was met when he wrote to his brother-in-law under his alias. Unknowing the name, the letter was returned to the post office. The postmaster James Smtih just so happened to recognise the writing, having taught Turpin to write and turned him in. He was wanted on counts of horse theft, which would lead to a death sentence.

The sentence was quoted by clerk Robert Appleford, with the newspaper’s praising “the offender’s being brought to justice.”

For his execution, Turpin brought new clothes and hired five onlookers for 10 shillings to avoid the ultimate embarrassment of no bystanders at his own execution.

Gruesomely, the slow drop execution was used in which the hanger would hang until strangulation, left as a display on the gallows. In 1910, The New York Times called this “a source of no little satisfaction to know that the notorious English criminal was properly hanged for his deeds.”

Character Rejuvenation

Once dead, Dick Turpin could very well have gone the way of many others, fading into a footnote in history.

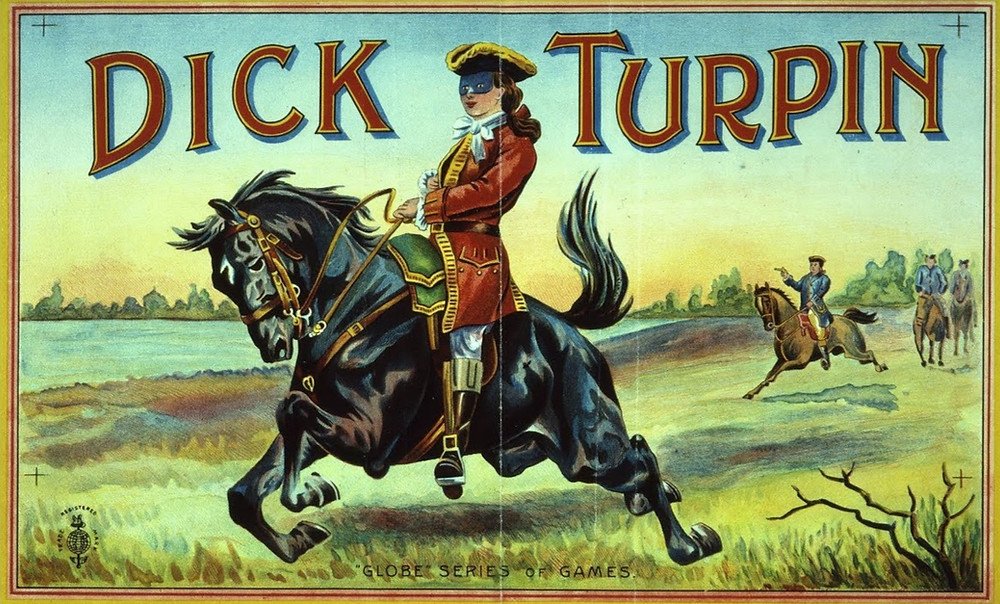

His name was brought back into the public light, largely attributable to one man: William Harrison Ainsworth, in his book Rookwood. The novel, from 1834, creates paints a sympathetic Turpin, likely aided by 1832’s abolishment of horse stealing as a death penalty-wielding crime – the main crime Dick was tried for. This was not exactly new with John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera pitting a heroic highwayman character.

This included fictitious stories such as the creation of Black Bess and the fabled ride from London to York in 15 hours. Although known by these tales, they are simply created to add to the character of Dick Turpin.

Subsequent cheap novels, called penny dreadfuls, capitalising on the embellished story of Turpin, idolising the character.

The famous 1906 poem The Highwayman has become perhaps the most definitive modern work, building sympathies of these thieves.

Now with the murderous acts gone, he has become more of a Robin Hood figure.

Music has not aided this image either, with some songwriters presenting Dick as a bold anti-hero. Many traditional ballads have become oral traditions in Britain whilst songs like ‘Whiskey In A Jar’, ‘Stand And Deliver’, ‘On The Road To Fairfax County’, and ‘Highwayman’ by Jimmy Webb are all associated with the theme of a romanced highwayman.

It also has to be said that comedy film or TV adaptions such as the role set to be played by Noel Fielding and the film Carry On, Dick do not exactly help the cause.

Epilogue

It seems that the re-established popularity and admiration for Turpin comes from the fact his death was due to now rather petty acts, namely horse stealing. However, that discludes the torturing and killing committed by the evil Turpin who is certainly not as depicted.

We talk about the injustice of those wrongly reflected in a negative light in their own time: Alan Turing, Derek Bentley, Galileo, etc.. How is it any better than centuries are terrorising the English public, Turpin is championed in our society?

History Extra states: “The image is a wildly romanticised fallacy but continues to transform brutish killers into ‘gentlemen of the road’.”

What we should remember above all is the horrible injustice of the beloved highwayman who killed and tortured.

Perhaps History Press described it best when they said: “Now many years on we are far removed from his evil deeds, and so choose to gloss over them in favour of a more palatable version of historic events – for tourism’s and legend’s sake. Skirting around the historic facts of Turpin’s cruel actions and violent ways, we instead choose to dwell on his outsider personality, romanticise his exploits and admire his rebellious nature.”

GRIFFIN KAYE.