As much as it pains me to say it as an Englishman, Wales truly is one of the great countries of the world. A quaint country, the nation rose from working-class roots with the mining country producing some of the greatest actors, music, and comedians of the last century. That said however, it has not all been smooth-sailing as with the infamous 1966 Aberfan Disaster, the worst British tragedy of the last century.

About Aberfan

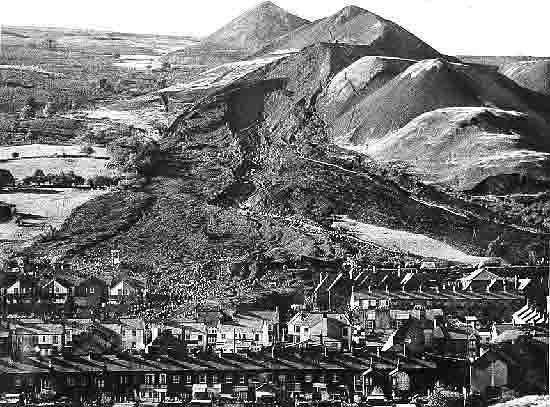

Aberfan would not at all have looked out of place in 1960s Wales. A small mining village, it is toward the bottom of the western valley slope of River Taff and on the eastern slope of the Mynydd Merthyr hill.

Rich in coal, the Merthyr Vale Colliery was set up in the mid-late 19th century.

Build To Disaster

The tyrannical National Coal Board (NBC) had had many complaints prior to 1966.

Spoil tips were deposited on slopes on top of the village of Aberfan. Seven spoil heaps had formed by 1966 with an estimated two million cubic metres or 2.6 million cubic yards. Only number seven was in use and was over 110 feet high with nearly a quarter of a million cubic metres of spoil or enough to fill the Royal Albert Hall two and a half times over.

How did NBC manage to do this? Complaints were present but as the BBC noted the reply to the dangerous positioning of tips was “make a fuss and the mine would close”. The NCB were hostile to any criticisms asking for the removal. The village relied so heavily on mining, that removal of the industry would be even worse so they just had to accept their lot.

The Black Mass Avalanche

The weeks leading up to the disaster saw 6.5 inches of rainfall. In tip seven too were tailings, which when mixed with water had a quicksand effect.

In the early morning, miners had noticed part of tip seven has sunk but nonetheless, it passed their test as they headed off for a tea break.

Observer Glyn Brown commented: “What I saw I couldn’t believe…It started to rise slowly at first…I thought I was seeing things. Then it rose up…at a tremendous speed. It sort of came up out of the depression and turned itself into a wave – that’s the only way I can describe it – down towards the mountain… towards Aberfan village… into the mist.”

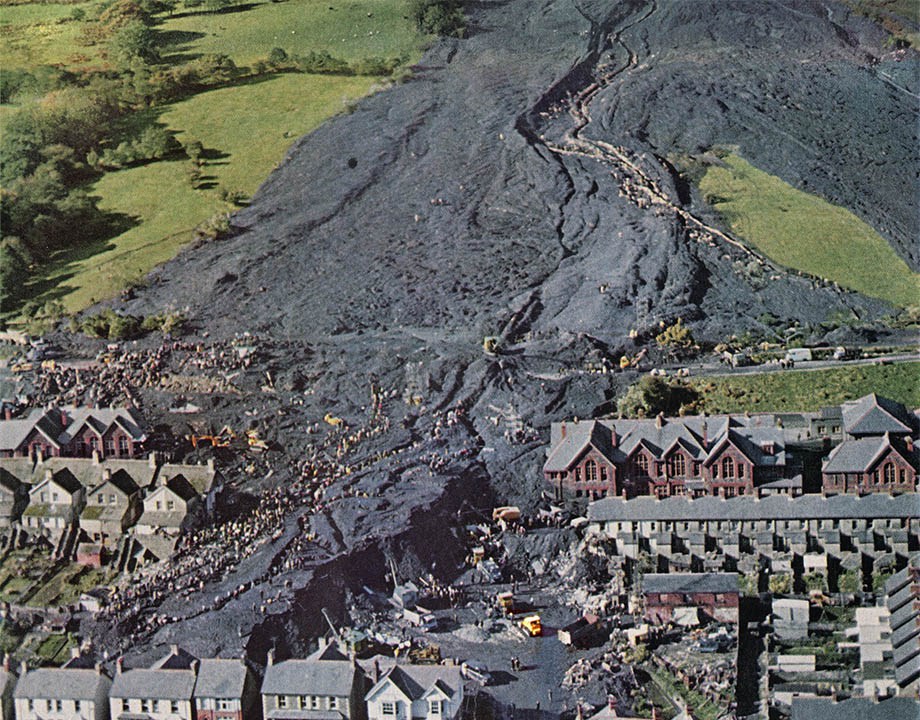

At 20 miles per hour, the waves of black doom poured down at heights of 30 metres, which would engulf anything below.

The first victims of this brutal tsunami of blackness were owners of two cottages on the outskirts of the village, killing those inside instantly. Water mains too were broken as it continued moving down, demolishing 20 or so terrace houses.

Devastation In Pantglas

Cut to the Pantglas Junior School on the morning of October 21st 1966 at 9:15.

It was the last day of school before the half-term, a half-day actually. Just a few hours until an extended break so the children settled down for register having arrived just a few minutes earlier.

A low rumble continued sounding louder and louder. A survivor described it as “like a thunder or a jet aeroplane” before seeing a “black mass”.

The chaotic avalanche not only knocked in the roof and walls, destroying glass and flooding into the rooms but the mixture of water with the tailings created a cement-like surface, which would only hinder searches for survivors by trapping the innocent kids.

Simply put, it was a catastrophe. Half of the village’s children died.

The last surviving child to be rescued on that day remarked “Most of my friends in my class died. Basically, we were happy-go-lucky children looking forward to the half-term holidays and at 9:15 our childhood stopped.”

Had the incident taken place an hour earlier, the school would have been empty, the same had it happened three hours later or in the next week. The worst possible time to strike is when it struck.

The event is captured in all its horrific, petrifying callousness in a scene from The Crown – with the whole episode a hard one for actor Jason Watkins to film, having lost his own two-year-old child.

In all, 144 people died as a direct result. 116 of these were children Most of the fatalities were those aged 7-10, with ages as young as three months to 83 years all sadly perishing.

Dinner lady Nansi Williams deserves the utmost praise, throwing herself over five children to try to save them; she died instantly yet due to her heroic efforts, they all survived.

George Williams, who was trapped in the wreckage and rubble commented: “In that silence you couldn’t hear a bird or a child.” A mother of a deceased victim said many years later, “You could always hear children outside playing…for a couple of years afterwards, you couldn’t hear a thing.”

Aftermath

The first call was placed at 9:25, about 10 minutes after the school’s destruction.

The New York Times documented: “Civil defence teams, miners, policemen, firemen and other volunteers toiled desperately, sometimes tearing at the coal rubble with their re hands, to extricate the children.”

Desperate diggers continued, with some 2,000 trying their best to salvage the living from the carnage. Some worked endlessly for 10 hours although it was almost inevitable that the longer the search stretched, the less successful results it would yield. In fact, no one was found alive after 11am.

Others gifted services such as 400 embalmers who helped clean corpses and a Northern Ireland group who removed as many plane seats as possible to accommodate as many children’s caskets as possible, helping the post-disaster efforts.

The Media & Press

The event was an early example of a television sensation. The news was spread by this largely new form of communication, with the event quickly becoming national news.

Acclaimed presenter Cliff Michelmore stated of the event as it transpired “Never in my life have I ever seen anything like this. I hope I should never, ever see anything like it again.”

The UK raised £1.75 million, now (in 2022) well over £30 million. Nearly 90,000 individuals pledged through the Aberfan Disaster Fund in short order after hearing of the tragedy.

More public support was reflected in funeral figures. Although the speed in which funerals occurred differed with some taking place the very next day, the October 27th funerals of 82 victims, 81 of which were children, took place buried in a pair of 80-foot trenches; 10,000 attendees were present.

Also, as a result, the site attracted famous figures including then-Prime Minister Harold Wilson, of the Labour Party.

A notable absence was that of The Queen. The Queen did not visit Aberfan for eight full days. Although husband Prince Philip had visited, she did not, something that is apparently one of Her Majesty’s biggest regrets, in stark contrast with The Crown’s perception of The Queen’s crocodile tears. The people of Aberfan are nonetheless grateful and have remembered her showing, and expressing gratitude.

Music fans may know the events, inspiring the hit New York Mining Disaster 1941, a UK and US top 20 single for the then-largely unknown Bee Gees.

Villains Of The Piece

One of the most reviled parts of the whole Aberfan tragedy was the stubborn and pitiful dodging of any justice or responsibility of the National Coal Board.

The NCB, despite the many complaints of the locals to move the tip, claimed they were not responsible. They claimed it was a combination of geographical features and an act of God.

On top of this, they refused to move the tips, thinking it irrational despite obvious and reasonable calls to do so. Only when miners shuffled coal into offices did the NCB give in. Not their own money was used, instead they dipped their hands into the relief fund, allowed to use £150,000 of the publicly-donated money. The funds for the tips were only repaid in 1997, without interest.

The tribunal that oversaw this decisively commented that the NCB acted with “bungling ineptitude”. Yet the NCB saw no arrests, fines, or company personnel alterations. PM Harold Wilson described the report as “devastating”.

Public pressure mounted enough for the NCB to donate some money: £50. This poultry figure is still less than £1,000 today. Another £500 donation was added after press outrage, still not nearly as much as many believe should have been paid in reparations.

Wilson’s government did quickly write up the Mines and Quarries Tips Act of 1969 to prevent another incident of this magnitude – but of course, it was too late to stop this, even if it could stop other Aberfans.

Moreover, the NCB forced families to prove they were close enough to their own children before giving out the £500 payments.

The press also acted callously toward the locals, often to just print a good story. This includes a journalist asking a young child to cry over the death of her school friends as it would have made a good picture.

Epilogue

The generational gap present in Aberfan is a stark reminder of the horrors of the autumn of 1966.

What is to learn from Aberfan? Speaking personally, this is one of the hardest pieces to stomach that I have ever written about. 144 is a huge number from such a small village. The callousness of the NCB makes it even more unforgivable. We seem to forget this was so very recently, less than six decades ago and there are still living figures able to tell the chilling stories, making it all the more raw and melancholy.

What makes it even more chilling and terrifying is that these kids had heard their doom coming towards them. Indeed, these were not oblivious babies – they were screaming children well aware of the petrifying situation that was unstoppable about to change their lives, if not end it.

Perhaps the best takeaway was from local teacher Cyril Vaughan, when he retrospectively remarked: “This is what people have always got to be prepared to what out for, isn’t it? That industrialists do not take advantage of people in order that they may make a fortune.”